Some recent conversations with fellow writers have left me thinking about writing practices—mine, theirs, the overlaps and the in-betweens. I know writers who have created beautiful, devoted rituals around their writing; they wake every morning at 5:00 a.m. and spend those first dark hours of the day with a pen and notebook, or they sit down after breakfast with a fresh cup of coffee, a candle burning. And I know writers who don’t mean to write every day, but seemingly can’t help themselves, scribbling poems in the margins of books, jotting lines down on napkins or in the Notes app on their phone.

I’m not the type of writer who sits down at a desk at a certain time every day and tries to churn something out. I respect those kinds of writers—I see the benefit of the daily practice, making writing a habit, building the muscle memory of the image, the line, narrative. My writing comes in spurts and bursts; I go through long periods of drought in which no poems arrive. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve grown more comfortable in these periods of silence. I know that the poems, eventually, will come.

I’ve also stumbled upon other writers who have successfully busted the myth of “writer’s block” for me. I especially love this essay by Carl Phillips, which considers the role of silence for writers, and this part in particular:

I once asked Ellen Bryant Voigt, a poet for whom there are typically many years between books of poems, how she handled the silence, what I still thought of at the time as writer’s block. “That’s not how I think of it,” she responded, and went on to explain to me how a snake, in order to attack, must first recoil to establish a position from which to attack. As I understand the analogy, the attack is the act of writing, and the period of recoil, of retraction, is many things: reflection, thinking, revision of thought, remembering. “You’re not blocked,” Ellen told me. “You’re waiting. You’re paying attention.” Which is also research. Also, a version of silence, the only sound the sound of a snake breathing, which must be, as sounds go, a soft, a small one.

I love this emphasis on paying attention, making those periods of silence meaningful. Earlier in the piece, Phillips writes “I think that’s all art is, a record of interior attention paid.” When I teach creative writing, it’s with this in mind. We spend the first weeks of the semester doing things like keeping audio journals, smelling perfumes, visiting the campus art museum. As we move toward the page, it’s with a sharpened understanding of what attention means, and how our senses inform our experience and memory.

I’m a collector at heart. I love the process of gathering things—books, photos, notebooks, ephemera, perfume. It occurs to me now that this practice of collecting is also a practice of attention. There’s a desire to keep these things close to me, to hold them in some way.

That practice of collecting spills over into my writing life. I’ve come to think of my own daily writing practice as cataloging—gathering material for the moment when the need to write hits me. I do this in a few ways, most of them having to do with a rotating set of notebooks. Here are the notebooks I currently keep:

Daily journal: a medium-sized journal, this is where I put thoughts, feelings, anxieties, what I did that day, little observations, things people said. I return to these journals if I’m trying to write about a particular memory or period of time, sometimes mining the pages for details.

Poem notes: a smaller notebook, one that might fit in a pocket, I think of this as my “on the go” book where I write line fragments, pieces of language that caught my attention, ideas for poems or essays, images that stand out to me, quotes from something I’m reading, notes from poetry readings or art galleries, etc.

Word journal: Another smaller journal, I use this to keep lists of words I come across while reading—words that are interesting, beautiful, strange, etc. This becomes a major generative tool for me when I sit down to write. I use it often when I’m stuck in the middle of writing a poem, at which point I’ll browse through the words, looking for something that leaps out at me, then challenge myself to include that word in the next line of the poem. It’s a small enough constraint that gets the creative gears turning again.

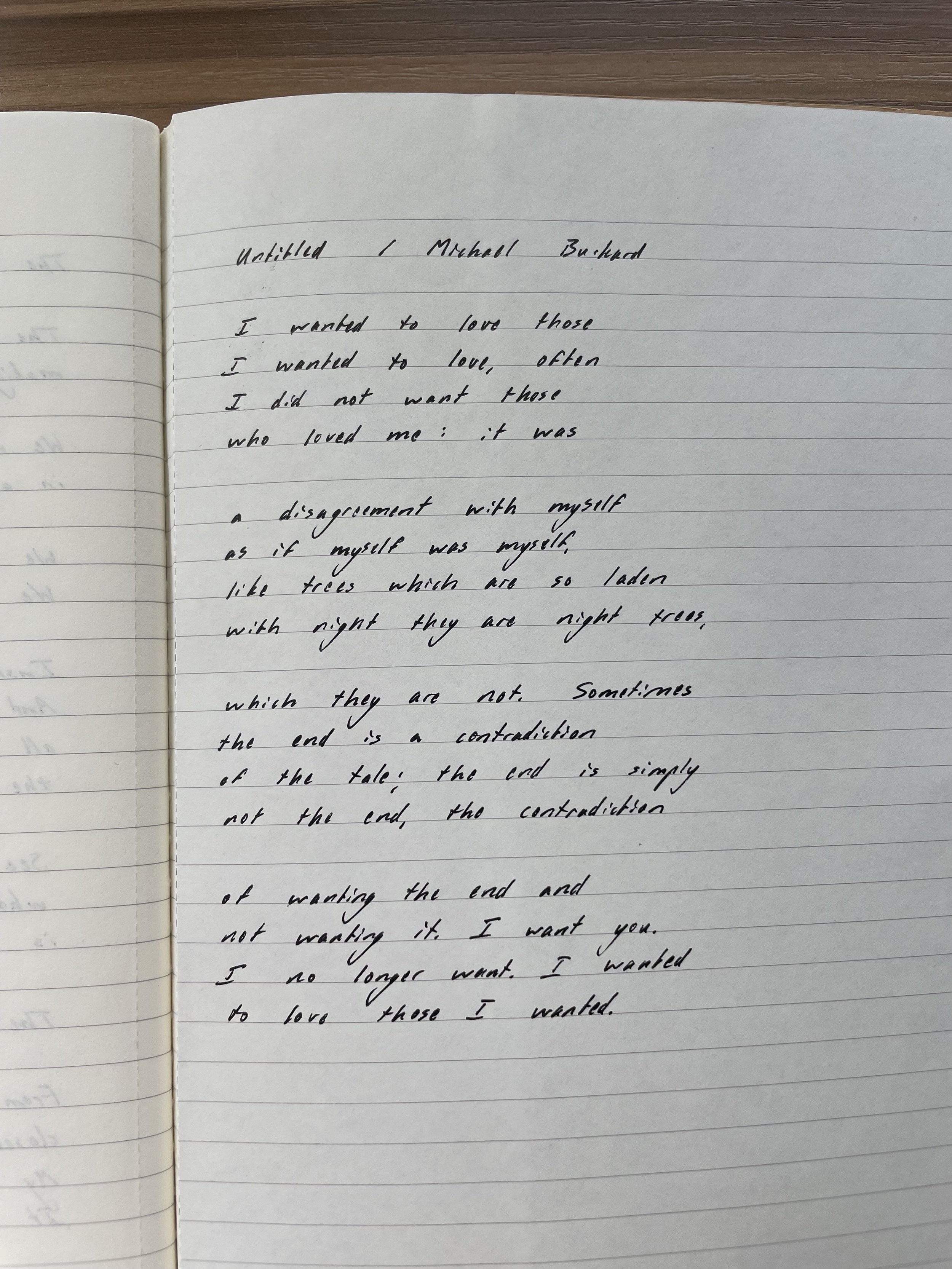

Poem journal: The largest of the journals, this is one I use to copy out poems which struck me, ones I want to spend more time with. I love the practice of slowly copying each word of the poem, savoring them as I go, thinking closely about the way the lines work together and how the poem moves. Here’s a page where I copied one of Michael Burkard’s “Untitled” poems—one which I’ve realized I copied at least twice into the same journal:

In addition to the written journals, I also keep an audio journal, which I’ll write about at length another time.

Finally, on the subject of writing practice, here are some books/essays I often return to:

bell hooks, Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work. In particular, the first essay in the collection (“Writing From the Darkness”) is a brilliant piece about diary-keeping as a tool for self-discovery and self-recovery. hooks writes: “However much the realm of diary-keeping has been a female experience that has often kept us closeted writers, away from the act of writing as authorship, it has most assuredly been a writing act that intimately connects the art of expressing one’s feeling on the written page with the construction of self and identity, with the effort to be fully self-actualized” (5).

Joan Didion, “On Keeping a Notebook.” This one seems obvious, but I can’t go without mentioning it. Here’s a favorite bit: “See enough and write it down, I tell myself, and then some morning when the world seems drained of wonder, some day when I am only going through the motions of doing what I am supposed to do, which is write — on that bankrupt morning I will simply open my notebook and there it will all be, a forgotten account with accumulated interest, paid passage back to the world out there”

Ted Kooser, The Wheeling Year: A Poet’s Field Book. This is less a reflection on a writing practice and more an example of what one practice of journal-keeping might look like—in this case, a sequence of short observational prose pieces organized by month. In the preface, Kooser writes, “I know from years of experience that keeping a journal is like taking good care of one’s heart.”

Mary Ruefle, Madness, Rack, and Honey. Oh, Mary Ruefle. How I adore the way you think. I love this bit from the title essay, which brings me back to Phillips’ thoughts on attention: “Recently I found myself filling out a grant application by writing: ‘I seek an extended period of time, free from all distractions, so that I might be free to be distracted.’ Distraction is distracting us from distraction. Perhaps we wish to be distracted by the slightest nuances of being, thinking, feeling, or seeing” (137).